Fauve Fever

- Evan Lai

- Mar 29, 2025

- 5 min read

ABSTRACT

Known as the ‘first avant-garde movement of the 20th Century’, Fauvism is widely regarded to be one of the first revolutionary movements towards abstract expressionism. Originating in France in the early 20th century, the Fauvists represented art that struck a new balance between compositional and technical elements, and also served as a capstone transitional stage for many artists whose style evolved from the Fauvist school of thought.

Beasts Abounding

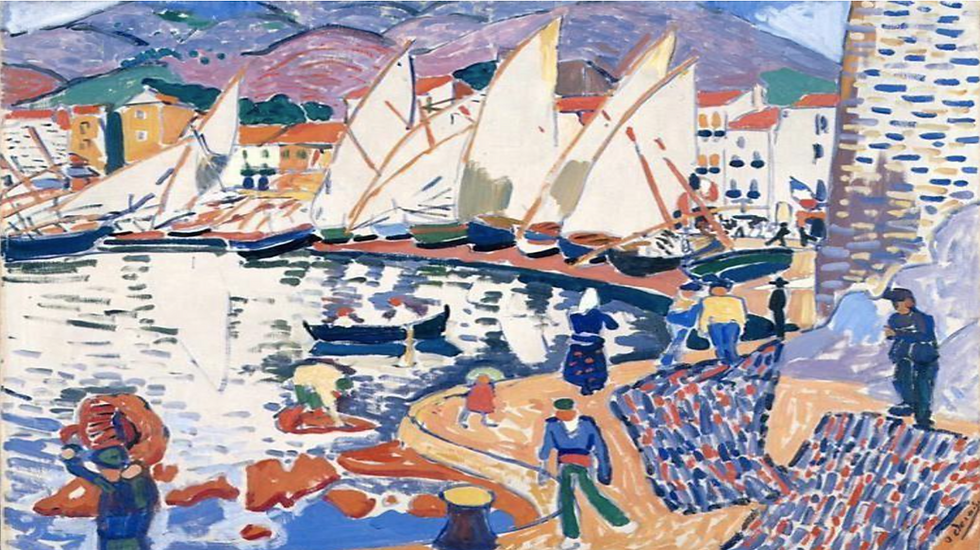

The term ‘les fauves’ (wild beasts) was first coined by art critic Louis Vauxcelles after seeing the work of Henri Matisse and André Derain at the Salon d’Automne (Autumn Salon) in Paris in 1905. The Salon exhibited the first Fauvist paintings from summer of that year, when Matisse and Derain collaborated to work on a new style in the small fishing port of Collioure on the Mediterranean coast in the South of France. It is evident why les fauves would be such a fitting term: the Fauvists developed a very distinctly emotional colour palette that was not representative of its portrayed environment, challenging the value and meaning of colour in their nouveau exhibitions. The Salon d’Automne of 1905 was one of three large-scale exhibitions of the Fauvists, along with the Salon des Indépendants of 1906 and the Salon d’Automne of 1906.

Fauve Fever Dream

‘How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow; this shadow, rather blue, paint it with pure ultramarine; these red leaves? Put in vermilion.’ Gauguin to Sérusier, 1888.

Fauvism had a radical goal of separating colour from its depiction of reality and allowed it to exist on the canvas as an independent element. The Fauvists had a strong belief that colour could project a mood within the work of art without having to be true to the natural world.

Members of the Fauves also shared the use of intense colour as a means of conveying the complex emotions the artist carries. This juxtaposed strongly against the artistic norms at the time, when Neo-Impressionism and Pointillism were still highly in style. Another of Fauvism's central artistic concerns was the overall balance of the composition. The Fauvists were highly attentive to simplified forms and saturated colours that made their works so definable and recognizable, incorporating their mantra clearly and distinguishing their works from those of other movements. This can be seen through the influence of colour theory in their works – particularly the use of complementary colours, which had also been developed near the end of the 19th century. When used side by side, colours thus appeared brighter. Another reason for the technical radiance is due to the use of bold colours that were often applied directly from the tube in wild loose strokes of paint.

Each element in Fauvism played a very specific role since the immediate visual impression of the work was very important and had to be strong and unified. Vivid brushwork and unnaturalistic, strident colours remained a point of consistency across the works of the Fauvists. However, above all, Fauvism valued individual expression. The artist's direct experience and emotional response to nature were more important than academic theory or traditional techniques. This marked a shift in the priorities of artists when creating art, recognizing the limitations of creating solely based on conventional artistic principles and furthering their intentions to more unconventional forms.

INFLUENCES

Henri Matisse was widely regarded to be the father of Fauvism. This style only gained prominence after Matisse had earlier experimented with the Post-Impressionist style of Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne, as well as the Impressionist masterpieces of Seurat, Cross and Signac. Furthermore, Matisse also adopted saturated colours and the complex brushwork of German Expressionists, which were also emerging around the time. He mentioned how 'you must forget all your theories, all your ideas before the subject. What part of these is really your own will be expressed in your expression of the emotion awakened in you by the subject.' Post-Impressionist work inspired Matisse to place an emphasis on colour and personal expression, who extended this technique and combined it with Seurat’s Pointillism. All these influences played a role in Fauvism’s rejection of traditional 3-dimensional space and the adaptation of flat areas and patches of colour to create a new pictorial space, as well as the unconstrained brushwork that is so definitive of Fauvist pieces.

Fauvism is also closely associated with the rise in Modernism at the time, when artists began to explore new methods of representing their environments instead of sticking to a repetitive, conservative art style. Furthermore, as globalisation began, African and Oceanic art became an inspiration for the Fauvists, which eventually branched off into Cubism. This is most evident in the bold colours and simplified forms adapted by the Cubists, who took abstraction a step even further and set the scene for more abstract art movements to come. Thus, Fauvism proved to be an important precursor to future art movements as well as a watershed for future abstraction. In addition to Matisse, other notable Fauvists included Braque, Rouault, Friesz and De Vlamnick. Compared to Matisse, De Vlamnick in particular employed an even freer, more natural style. The Fauves also created a very extensive body of work: including portraits, landscapes, mythology and nudes; in a variety of media, including: oil paints, watercolor, pastels and printmaking

LEGACY

Fauvism might have been short lived – with only three exhibitions and around 5 years of strong historical influence (1905-1910), but it never really perished. Instead, Fauvism continued to impact artists from then on, since it was more of a learning stage than anything that allowed young artists to freely develop their own unique style. As such, many rejected the ‘turbulent emotionalism’ of the Fauvists for Picasso and Braque’s Cubism logic in 1908. Art became analytical and technically professional for a while under Cézanne’s Post-Impressionism, but that was only for certain parts of the world. Derain also moved past Fauvism and adopted a more conventional neoclassical style. Matisse is the only one said to ‘carry Fauvism with him to the grave’. However, this vibrant emotional spirit of Fauvism lives on in the Expressionist works of Edvard Munch and Wassily Kandinsky, and even further into the modern day we live in now.

Other References:

Comments