WABI-SABI: Perfect Imperfection

- Eugene Lau

- Mar 21, 2025

- 5 min read

In a world that prioritises perfection and uniformity, artificiality tends to overshadow the organic. We often fail to appreciate the tainted windows of antique shops or the cracks in concrete walls that surround us daily. Yet, the sparse and the imperfect can be viewed as profound symbols of beauty. Characterised by visible signs of wear and tear, Wabi-sabi is a Japanese philosophy that revolves around the acceptance of evanescence and imperfections. An object’s existence is imbued with authenticity and its natural process of decay is thus appreciated aesthetically.

THE GARDEN TENDER

The Japanese story of the untended garden is commonly used to explain the philosophy of Wabi-sabi.

There once was a sprawling shrine whose vast gardens were left untended for too long. Covered with fallen leaves everywhere, the master instructed his student to prune the bushes and rake the leaves. ‘Make our garden perfect,’ the master said. After days of excruciating work, the garden was pristine where not even a single errant branch or weed on the ground could be spotted. The student pridefully asked the master to take a look at his carefully manicured garden. However, the master deemed his misguided effort erroneous and disappointing. Walking to the edge of the garden, the master grabbed a cherry tree and vigorously shook it as the student watched the cherry blossoms shower the cleanly tended garden. ‘Now it is perfect, student.’

WABI-SABI

What is Wabi-sabi?

Wabi-sabi is the imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. Rooted in Zen Buddhism, it is considered one of the most dated manifestations of minimalism in art where the aesthetic value in the worn over the new is emphasised. Straying away from the glorification of perfect, glossy and ornamented surfaces, Wabi-sabi puts forth the simplicity of everyday objects that fulfil a function rather than a form. In Japan, ‘wabi’ refers to the isolation and destitution of living in nature, while ‘sabi’ represents the beauty or serenity that comes with age and wear. Over time, these concepts have merged to bring to mind that nothing lasts forever, and that signs of age on an object can help us appreciate its value even more. It is these cracks and crevices that exhibit the lifeline of both natural and man-made objects as they are created and fall into decay.

The 7 Principles of Wabi-sabi

The elements of nature imbued in Wabi-sabi, like decay, reflect the virtues of human character and proper behaviour. It pays tribute to aesthetic ideals found in nature and the passage of time as overarching themes of existence; its ethical values extend beyond an art form to a way of living. The philosophy of Wabi-sabi is comprised of 7 principles: Kanso, Funkinsei, Shibumi, Shizen, Yugen, Datsuzoku, and Seijaku.

Kanso (簡素) represents simplicity or the elimination of clutter. Stripping away the superfluous, Kanso reminds us to prioritise clarity instead of decorative and non-essential elements.

Fukinsei (不均整) proposes the beauty found in asymmetry or irregularity. As in nature, asymmetries exist everywhere–tree branches are twisted and non-uniform; rocky beds in river streams are irregular and arbitrary. Despite asymmetries in nature, balanced and harmonious relationships are found. This principle is prominently exhibited in the Enso (Zen circle), where the circle is incomplete to symbolise the imperfection that is part of existence.

Shibumi (渋味) represents the beauty in the understated. Characterised by elegant simplicity, it strives to depict something in a direct and simple way without being flashy.

Shizen (自然) translates to naturalness or the absence of artificiality and pretence. Given the emphasis on ‘nature’, a paradox arises: The man-made ‘naturalness’ of the Japanese garden perceived by the viewer is in fact intentional and not natural. This deliberation underscores the importance of intention in the design of Wabi-sabi, and much like the natural feeling created in the garden, Shizen in this mindset is not a raw nature but one with intention and purpose.

Yugen (幽玄) refers to a subtle grace, evoking depth through suggestion rather than explicit revelation. It is the art of hinting at profound meaning without fully unveiling it, allowing the imagination to grasp what lies beyond the visible. In the Japanese garden, this principle manifests as a collection of nuanced, symbolic elements that subtly imply a deeper, more profound reality. Yugen can be understood as the essence of "less is more," where the absence of overt expression invites a richer, more contemplative experience.

Seijaku (静寂) refers to tranquillity and solitude. The garden provides us with this form of energised calm and stillness, away from noise and disturbance.

Datsuzoku (脱俗) denotes freedom from habits. Escaping ordinary routines, it detaches the human experience from reality as a form of ultimate surprise. The raw materials and arrangements of nature in the Japanese garden produce surprises that await us at almost every turn.

Applying Wabi-sabi

‘Pared down to its barest essence, wabi-sabi is the Japanese art of finding beauty in imperfection and profundity in nature, of accepting the natural cycle of growth, decay and death. It’s simple, slow, and uncluttered - and it reveres authenticity above all,’ Tadao Ando explains, a revered Japanese architect known for his pioneering works that involve the use of natural light and adhere to natural forms of the landscape. ‘Through wabi-sabi, we learn to embrace liver spots, rust and frayed edges, and the march of time they represent.’

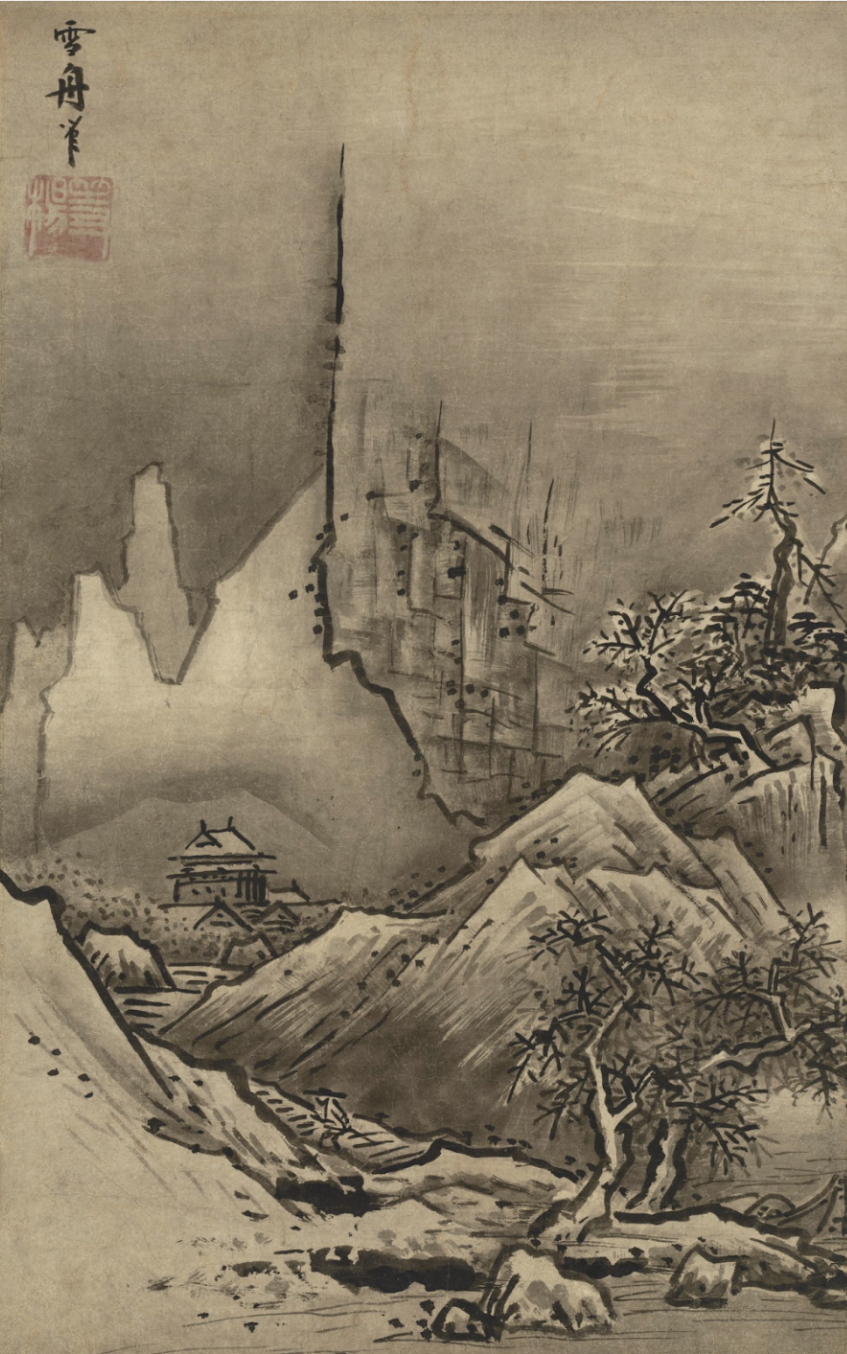

Aesthetically, wabi-sabi emphasises the use of natural materials such as wood, stone and clay, embodying a handmade or rustic quality. In pottery, marks and cracks adorn the earthy surfaces of ceramic vessels. Kitsugi (金継ぎ) is a common Japanese practice manifesting this principle: The art repairs broken pottery by repairing areas of breakages with urushi lacquer which is often mixed with powdered gold or silver. In traditional ink wash paintings, minimalistic, asymmetrical compositions are used to convey a sense of impermanence and tranquility. Sesshū Tōyō was a Japanese Zen monk and an ink master whose Winter Landscape series employ mostly organic, curvilinear lines and jagged brushstrokes. Despite embodying a harsh coldness, the series conveys serenity.

Wabi-sabi in the architecture of Tadao Ando

Wabi-sabi is also closely intertwined with architecture, often expressed through the beauty of ageing or decay. However, architect Tadao Ando offers a unique interpretation of organicity within this aesthetic. Unlike traditional wabi-sabi, which often relies on rustic, fragile, and organic materials, Ando predominantly uses concrete, steel and glass. His approach reflects a distinct philosophy rooted in the Japanese reverence for nature—not merely as a source of organic beauty but as a powerful force inhabited by countless deities. Ancient Japanese believed that exploiting nature would invite misfortune as nature would retaliate; for instance, excessive logging could lead to devastating mudslides during heavy rains. Ando embraces this perspective, viewing nature as both a blessing and a potential threat.

In his design process, the first step is to "read the site," not to dominate or exploit nature, but to find the most harmonious way for humans to confront its raw, unfiltered face. Ando’s designs deliberately avoid excessive comfort—some of his buildings allow rain to seep in or rooms to remain cold. He even advises clients to layer up to endure the natural chill welcomed into their homes through his designs. By encouraging residents to adapt and live with what they have, Ando challenges them to coexist with nature in its most honest, unadorned form. This approach redefines wabi-sabi not just as a celebration of decay but as a profound acceptance of nature’s dualities.

Other References:

Comments